CNN

—

A few minutes after taking the stage, a featured speaker at a conference poses a question to the audience: Does anyone here have more than seven kids?

In many circles, asking this would be strange or surprising. But at this kickoff dinner, it’s a clear crowd-pleaser.

Over the din of clinking cutlery, someone shouts out, “Nine!”

“Can anyone beat nine?” the speaker says with an auctioneer’s flair. “Alright, nine has it. Congratulations!”

As the crowd responds with cheers and applause, the audience member with the winning answer adds that their 10th child is on the way.

Welcome to the Natal Conference, NatalCon for short, where a big item on the agenda is boosting birth rates.

Some 200 of the most fervent supporters of a budding movement are here, hoping this in-person meetup will help their cause find an even larger audience — before it’s too late.

Many in this group are unlikely allies who share a common goal. Birth rates, they say, are plummeting to dangerously low levels, posing risks to the economy, services like Social Security and even the future of civilization itself.

And as they see it, getting more people to have more babies is the only solution.

Pronatalists are having a moment, buoyed by Elon Musk’s frequent social media posts amplifying their message and early policy moves under the new Trump administration, such as Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy’s memo promising more funding to places with higher birth rates.

The Assignment with Audie Cornish

Why Elon Musk Wants You to Have More Kids

A growing number of tech leaders, conservatives, and social influencers believe falling birthrates pose an existential threat to civilization, and this “pro-natalist” movement wants Americans to start having more babies. Audie talks to Brad Wilcox, a sociology professor at the University of Virginia. His book is called, “Get Married: Why Americans Should Defy the Elites, Forge Strong Families and Save Civilization.”

Feb 27, 2025 • 35 min

…

The momentum isn’t lost on organizers of this conference, who say the two-day event drew twice as many attendees this year as their first meeting in 2023, despite a steep $1,000 price tag for admission.

Organizer Kevin Dolan says pronatalists’ overall goals should be an easy sell. But in some circles, they aren’t.

“There’s a civilizational catastrophe coming,” he tells attendees this year, “and the way to solve it is to have sex? Like, that’s got to be the easiest pitch in history. So why do we have people practically clawing their eyes out they’re so furious that people are advocating for this?”

In many ways, NatalCon is a typical conference scene: The nametags. The pasta salads. And a seemingly endless stream of PowerPoint presentations.

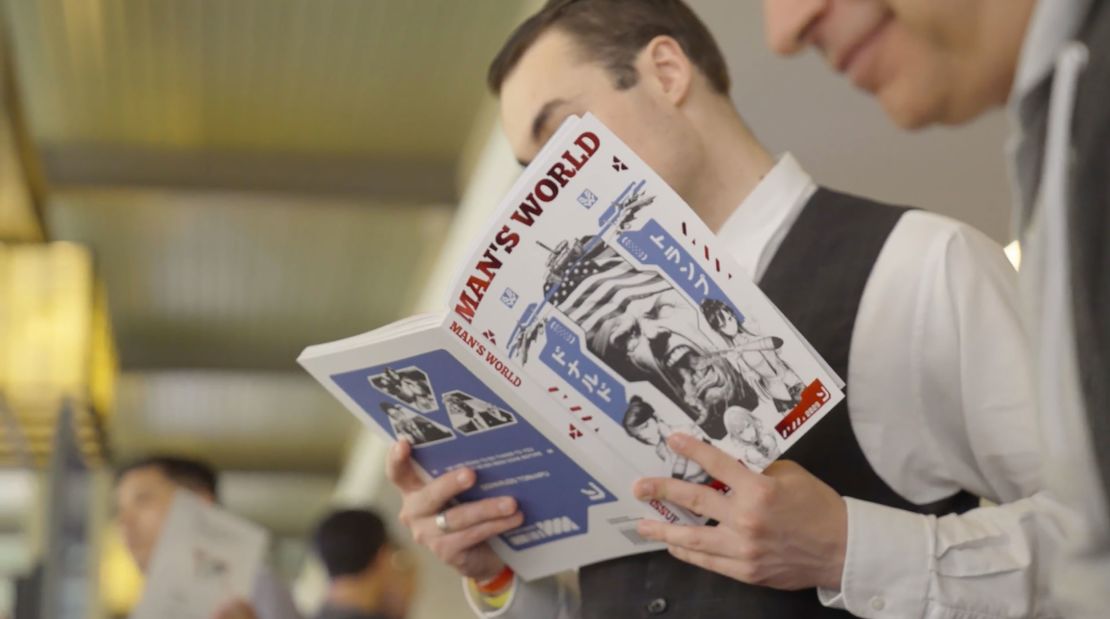

But in some ways, this gathering is notably different from others you might expect to see in the halls of a convention center. A childcare option was offered along with admission. Kids roam the halls at mealtime. Singles looking to find a like-minded match are wearing yellow wristbands. Attendees are leafing through copies of Man’s World magazine in the hallway.

The mix of speakers includes professors, alt-right provocateurs and internet personalities. And on the first day, an angry handful of protesters are outside, accusing attendees of racism and promoting eugenics.

“I love that there’s kids here at the hate conference,” far-right activist Jack Posobiec quips in his opening-night remarks. “You know, this massive ‘hate group’ that we’ve all put together, and yet, in fact, it’s actually just a bunch of like, moms and dads and families.”

It isn’t long before Posobiec’s speech takes on a more dire tone. He points out that birth rates in the US, Australia and Europe are declining.

“If we don’t reverse the tide,” he says, “there are challenges, and there are dark clouds on the horizon. Everything that we have worked for and built, the cathedrals would crumble, the Constitution would fade, the West would become a memory, a footnote in someone else’s story.”

This is the war for civilization, and we are going to win it, one life at a time.

Jack Posobiec in a speech at the Natal Conference

Pronatalism, he tells the crowd, is the last line of defense in a battle for the West’s survival.

“The stakes are nothing less than everything. This is the war for civilization,” he says, “and we are going to win it, one life at a time.”

It’s been nearly a year since Musk shared organizer Kevin Dolan’s speech from the last NatalCon with his millions of followers on X, his social media platform. Dolan, a Mormon with six children and a seventh on the way, says that “undisputably” brought more attention to the issues he’s trying to spotlight.

Demographer Lyman Stone, who’s one of the speakers at this year’s conference and director of the Pronatalism Initiative at the Institute for Family Studies in Charlottesville, Virginia, says Musk’s influence in the conversation is clear. He points to a chart measuring online searches for pronatalism-related terms over time. There’s a point in 2023 when interest spikes. “It gets Elon-ified,” Stone says.

“You have one of the world’s most powerful and influential men, controlling one of the world’s central disseminating points for ideas and information, really promoting the idea that low fertility is a major social problem. And I agree with him. It is,” Stone says.

Women are having fewer children than they want, Stone argues. And if something doesn’t change, he says, that will lead to numerous social and economic problems down the line.

“People aren’t getting the life they want…but also, there are material consequences of falling fertility,” he says.

Stone says he doesn’t always agree with Musk’s views. But the billionaire’s frequent posts on the issue, he says, have brought far more attention to it.

“He’s made it much harder to ignore,” Stone says.

Some pronatalists bristle at Musk’s approach to the issue in his personal life; the billionaire has publicly acknowledged fathering at least 13 children with multiple women. But they appreciate his devotion to their cause.

The day this year’s NatalCon began, Musk gave an interview to Fox News. He didn’t mention the event, but when asked to share the biggest worry keeping him up at night, the billionaire pointed to falling birth rates.

“Nothing seems to be turning that around,” he said. “Humanity is dying.”

Many scholars who study population growth say pronatalists’ concerns about a looming civilization collapse are overblown.

In the US and around the world, families are far smaller now than they were decades ago. And in many countries – including the US – birth rates have dipped below the replacement level of 2.1 children per woman, which is the rate countries need to maintain stable population numbers, without accounting for migration. Experts estimate that by the end of this century, the population of almost all countries in the world will be declining rather than growing.

But that doesn’t mean we’re on the verge of a catastrophe, according to Philip N. Cohen, a sociologist and demographer at the University of Maryland.

Even as birth rates decline, he says, global population growth is projected to continue for the next 50 years. And even after the world’s population peaks, the sizeable drop predicted would occur over hundreds of years, he says.

“What will happen is over the next couple of hundred years, the world population will fall down to where we were about 30 years ago… No one ever thought six billion people was too few. I’m not worried about that,” he says. “We’ve got environmental reasons to think that’s good. We’ve got economic reasons to be concerned about what that process looks like. But we’ve got a lot of problems, and that’s pretty far down the list.”

No policy can increase the number of babies born yesterday.

Philip N. Cohen in an op-ed criticizing pronatalism

In the short term, he says, there’s another way to shore up working populations as societies age: immigration. In fact, Cohen says that’s the only option, because the population will age more quickly than any babies born today can become workers.

“No policy can increase the number of babies born yesterday,” Cohen wrote in an op-ed last year criticizing pronatalism.

Karen Guzzo, a professor of sociology and director of the Carolina Population Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, says she sees herself as an anti-pronatalist.

“I don’t think we should try to make people have kids. I don’t think we should try to make people get married. I think there are small nudges we could do that might raise the birth rate — you know, if we had a better safety net, if we had paid leave and paid childcare, but also economic mobility, things that make people feel certain about their future,” she says.

Around the world, she says, efforts to push pronatalist policies to boost birth rates have faltered.

“It just doesn’t actually work. There have been all sorts of efforts. Some of the East Asian countries have things in place that we Americans would die to have — like these long, extended leaves, access to fertility treatments…childcare availability,” she says. “But they haven’t changed the work culture, and they haven’t changed men’s roles, and so it’s not enough.”

Skeptics of pronatalism are difficult to spot inside this closed-door conference, where a handful of security and staff are screening attendees. But a small group of protesters is chanting outside on day one, accusing attendees of racist and Nazi sympathies.

“Behind a thin veil of pseudoscience and intellectualism, this event gave a platform to fascists, race scientists, and far-right ideologues who openly promote population control, racial hierarchies, and authoritarian rule,” Arshia Papari, a spokesperson for the Austin chapter of Students for a Democratic Society, which organized the protest, told CNN in an email.

Some at the conference joke about the small protest turnout. Others seem on edge and are hesitant to speak with media covering the event. One man tells CNN he followed friends in the tech industry to this event “by accident” and fears he could lose his job for attending.

Ahead of the conference, press coverage called out some speakers as “race science promoters and eugenicists,” and students accused the event of hosting Nazis.

Dolan says he sees those labels as “white noise.”

“I’ve heard those words used to describe people who I just I know to be incredibly empathic, people who love everybody, people who want everybody to succeed, people who have no correlation whatsoever to any of the movements that are being described by those words ostensibly,” he says. “And so yeah, you just can’t be governed by people calling you names.”

Still, he says it’s no surprise some at the conference are camera-shy.

“People are afraid of being mischaracterized. … Even I have this trepidation about this thing that I’ve poured my heart into being sort of raked over the coals and mischaracterized and used as ammunition in this fight that I think is kind of fundamentally wrong-headed,” Dolan says.

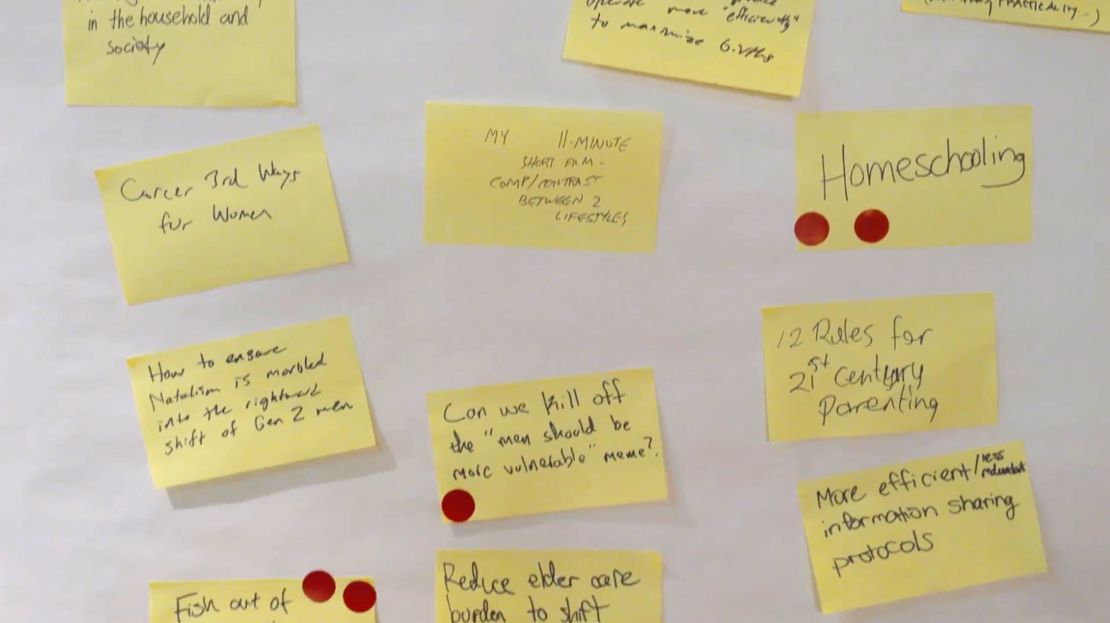

Dolan and others attending the conference say it’s common for people here to agree on big-picture problems. But there are plenty of ways they don’t see eye to eye. And that’s part of the point.

“You’re going to hear ideas that you disagree with. You’re going to hear ideas I disagree with. And I don’t think that it is appropriate to rule people out when they are coming in good faith to address a problem of this magnitude,” he says.

You’re going to hear ideas that you disagree with. You’re going to hear ideas I disagree with. And I don’t think that it is appropriate to rule people out when they are coming in good faith to address a problem of this magnitude.

Kevin Dolan, Natal Conference organizer

Dramatically disparate groups are finding space in the pronatalist scene, according to Catherine R. Pakaluk, an associate professor of political economic thought at the Catholic University of America who’s authored a book exploring why certain women choose to have large families.

“It’s pretty difficult to draw a neat, tidy circle around everybody here,” she says. There are those on the extreme right, she says, and those who favor more immigration. There are tech bros who favor science like artificial wombs and in-vitro fertilization. And then there are “Trad Catholics and Mormons,” she says, “people who really believe strongly that marriage is between a man and a woman, and the children that they have together.”

For her part, Pakaluk says she doesn’t agree with many of the views others at the conference espouse but wanted to come and present her research.

“One of the things that often gets skipped over in any discussion of natalism today is kind of the actual lives of women who make decisions about whether or not to bring a child into the world,” she says.

Dan Hess, a writer and father of six who regularly posts his analyses of declining birth rates under the X handle @MoreBirths, says diverse viewpoints are necessary to solve what he sees as a problem of epic proportions.

“It does not get solved without a big tent,” he says. As word spreads, Hess says he hopes more liberals will join the largely conservative conversation.

Writer and public policy consultant Paul Constance says that’s why he’s at NatalCon.

“The politics of most of the people who are here are abhorrent to me,” he says. “But that’s not the reason I’m here. I think it’s a really big, big topic, and progressives need to be in the conversation.”

Simone Collins weaves through the halls with a bonnet on her head and a baby strapped on her back.

She and her husband, Malcolm, have fashioned themselves into the public face of pronatalism. They head a foundation dedicated to the cause. And many attendees at the conference say they heard about it from the couple’s podcast.

The bonnet is attention-grabbing — an ironic clapback at critics who invoke the oppression of bonnet-wearing characters in “The Handmaid’s Tale” when they hear pronatalists’ points.

“Two things can be true at the same time. Malcolm originally convinced me to get a bonnet to troll people, and then I realized — wait, a hair covering is really useful when you’re doing really messy housework and when there’s all these other factors. So I wear it both to troll, and because it’s useful,” Simone says.

But unlike the dystopian fiction they hope her attire will invoke, the Collinses stress that, in reality they don’t want to force anyone to have kids who doesn’t want to.

“This movement isn’t about shaming people into having kids or convincing people with no kids to have one or two,” Simone says. “It’s about making it easier for families to have the family size they want, because people are not making that number anymore.”

If more isn’t done, she says, the world’s diversity will suffer.

“What we’re heading toward, clearly, based on many localized birth rates, is a mass extinction event of cultural and ethnic and societal diversity,” Simone says. “That is really scary. I want a future in which there are thousands of different subgroups, not three.”

What we’re heading toward, clearly, based on many localized birth rates, is a mass extinction event of cultural and ethnic and societal diversity. That is really scary. I want a future in which there are thousands of different subgroups, not three.

Simone Collins

If such dire predictions are true, why, then, are so many scholars pushing back against pronatalists’ concerns?

Malcolm Collins claims many demographers are simply lying about the severity of the situation because it doesn’t square with their beliefs.

He also argues it’s “intensely unethical” to rely on immigration to solve the problem.

“As a wealthy country, yeah, we can continue to drain these other countries and dry up their talent pools. … but we are astronomically screwing these countries over,” he says.

The Collinses have four children and a fifth on the way. Because of health issues, the couple says they’ve used in vitro fertilization to grow their family. They openly discuss testing and selecting embryos for health and personality traits — and they’re often accused of using pronatalism as code for eugenics.

Simone Collins says that’s an inaccurate comparison.

“This is just people choosing among their own embryos. We’re not talking about sterilizing people or all the classic problems that are out there with eugenics,” she says.

Benjamin Detry, 19, doesn’t have any kids yet. But he tells CNN he’s hoping to have at least five eventually, and here at the conference, he’s looking for a partner.

Detry is one of numerous attendees wearing the yellow wristbands organizers hope will help singles pair up. He says he drove to Austin from Houston, where he’s a college student, and spent his savings to attend the conference. But now that he’s here, he’s not sure about his prospects.

“There’s a lot of lads here. There’s not that many ladies,” he says. “So I wonder how the matchmaking event is going to turn out. Maybe it’s going to be kind of like a Coliseum battle, you know, like where the winner takes all.”

Simone Collins tells us there’s a good reason fewer women are at the conference than expected. At least six speakers dropped out of the event, she says, because they were pregnant.

“People are putting their money where their mouth is. Their family comes first,” she says, “and that’s what pronatalism is all about.”

There’s no Coliseum battle on NatalCon’s agenda. But in addition to the wristbands, the conference is offering sessions on dating, courtship and matchmaking – some led by Simone.

Organizers say they’re hoping to help foster real-life connections that are hard to find in today’s app-driven dating landscape.

Constance, the policy consultant, says his 29-year-old daughter had joined other liberal family members in mocking him over his participation in NatalCon. But she had a surprising reaction when she learned about the conference’s matchmaking side.

“She said, ‘If you find any viable candidates, here’s a photo you can share.’ That’s how bad the dating scene is,” Constance says.

That’s one area, at least, where pronatalists and critics of this movement may agree.

CNN’s Catherine E. Shoichet reported from Washington. CNN’s Meena Duerson and Deborah Brunswick reported from Austin.